What is a social actor?

- Michael Farrelly

- Oct 21, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 22, 2025

This question—what is a social actor—is an important one that we, as people doing text and discourse analysis, should take seriously. It is a question that we should address before getting into the details and procedures on how and why we analyse the ‘representation’ of social actors in text and discourse. This is because understanding what we mean by ‘social actor’ will help us to be clearer than we might have been about those details and procedures:

Our reason for analysing the representation of social actors in text and discourse;

Our method for doing so (the parameters of the analysis, the analytical categories we will employ, our presentation of results);

Our framework for interpreting our results;

Our critical stance on this interpretation.

In the CDA literature on analysing the representation of social actors, there’s little definitional work to be found on social actors. Perhaps it seems obvious what is meant by a social actor; I tend to think that being specific helps us in the ways I’ve just set out above. In simple terms, a social actor is a participant in social events (raising the question ‘what is a social event’?— which may be a topic for another series). And this might be good enough if your project is one of mapping a text or discourse— or if you have a practical critique of a situation, an idea of who should be a participant but is not. But is there a way to emphasise the critical importance of social actors?

In general, I’m interested in understanding what we, as societies, are doing well and what we are doing badly. I want to understand this because I also want to know how we can do more of the good and less of the bad. The relevance of social actors here is that they are the ones who are ‘doing’ the good and the bad, and they are the ones who are acting, or failing to act, and they can be the ones exerting influence one way or another.

Societies, and the conditions they present, change; and this change can be influenced by people.

For me, this is the crux: social actors have the potential to have volition. They exercise their volition or do not—how and why would be a question for research. And as social actors, they occupy a social position from which they are more or less able to exercise their will—again, how and why would be a question for research.

For any given situation that we seek to analyse in critical social science, therefore, we should also seek to understand the characteristics of the people involved and the ‘acts’ they undertake. We should seek to understand their capacity for volition.

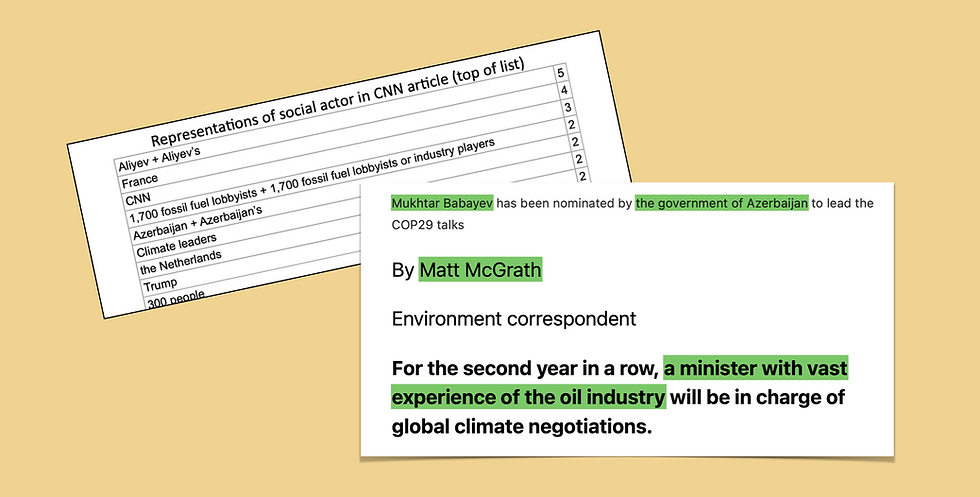

As critical discourse analysts, we can then analyse the representation of social actors in text and discourse and, depending on the situation we are critically analysing, compare representations with actual capacities for, and enactment of, volition. We can analyse and interpret the likelihood that textual and discursive representations of social actors affect actual capacities for, and enactment of, volition.

In short and simple terms, then, as a critical discourse analyst, I’m concerned with who has the power to use their will and who does not; and I’m concerned with the extent to which texts and discourse are a factor in facilitating or curtailing this power.

Comments