Experience: CDA - THE Tool for Uncovering Covert Truths

- Thomas Branagan

- 12 hours ago

- 2 min read

My experience in Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) during my undergraduate studies provided me with an avenue of inquiry for my MSc in Social Research, allowing me to draw concrete, unique conclusions which significantly enriched my master’s dissertation.

My undergraduate dissertation was a CDA of the speeches delivered by G7 leaders at COP 27. I found that there was an overall theme of national competition in these speeches - leaders spoke about climate change in terms of a competition between nations and made claims that their nation was ‘winning’ this competition.

I also sought to identify and map the manifest intertextuality within their words - an analysis that proved rich across all texts examined. Among various compelling findings, my analysis revealed a strong trend of intertextuality being used to marginalize or delegitimize China and middle eastern states. The type of texts used to bolster these remarks were usually demonstrably ambiguous and outdated geopolitical narratives, or the quoting of statistics from unnamed sources which referred only to territorial emissionswhile ignoring the fact that a significant portion of the west’s consumption-footprint can be traced to eastern manufacturers (as recently as 2021, China was the single largest importer to the UK). The sheer extent of the evidence made for a potent argument. This dissertation was well-received, and the method and theory of CDA stayed with me.

I went on to study at postgraduate level. The master’s in social research that I took focused on various useful methods of textual analysis, however, CDA was absent from the curriculum—a notable omission, I felt, because no other tool I encountered had the same rigorous ability to expose covert truths within and across texts.

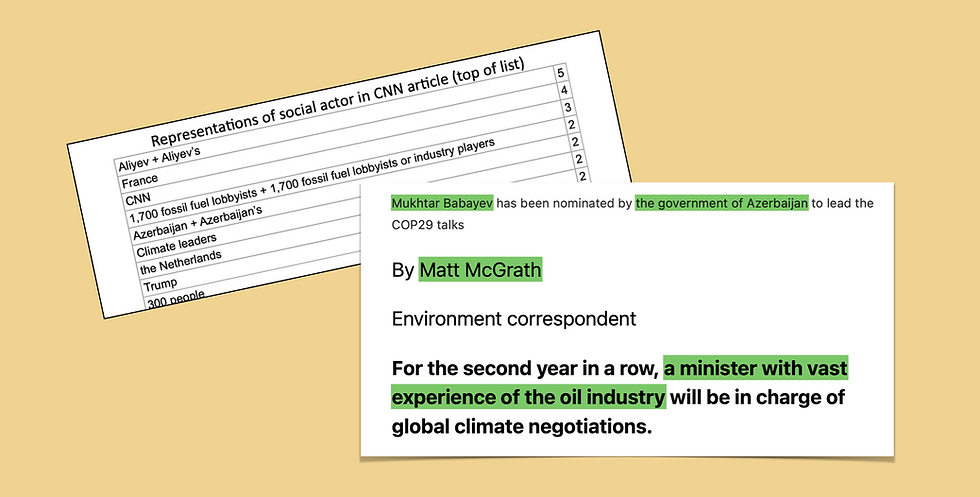

For my master’s dissertation, I was required to design and execute a project involving the collection and analysis of primary data. I asked nearly a hundred people about climate and environmental issues, their political beliefs, and their preferred sources of news and information. Open-ended questions were designed to elicit extensive textual responses, which I then subjected to a standalone CDA focused on two language features: intertextuality and social actors.

I initially expected to find a significant disparity between public views and political speech. However, while 70% of my project’s participants expressed a strong dissatisfaction with the efforts of western governments, I also found a distinct reflection of political rhetoric in the public’s attitudes toward China and the Middle East. Crucially, a sizable number of participants actively referenced or quoted the same outdated or inaccurate information I had identified in the G7 speeches when articulating their own criticisms of these geopolitical actors. Namely, sixteen separate participants criticized China’s environmental actions in comparison to the UK’s own even though they were not asked explicitly to discuss the actions of specific nations.

Had it not been for my undergraduate project, this occurrence would not have stood out – it wasn’t as though most participants recited these views. However, my recognising of the phenomenon in a fair amount of the responses allowed me to identify a notable and justifiable cycle: erroneous and arguably damaging political opinions are reproduced and consolidated through texts generated by governments, the media, and ultimately, the public. This demonstrated an interdiscursive feature of overall climate attitudes which I don’t believe could have been identified or proven with any approach other than CDA.

Comments